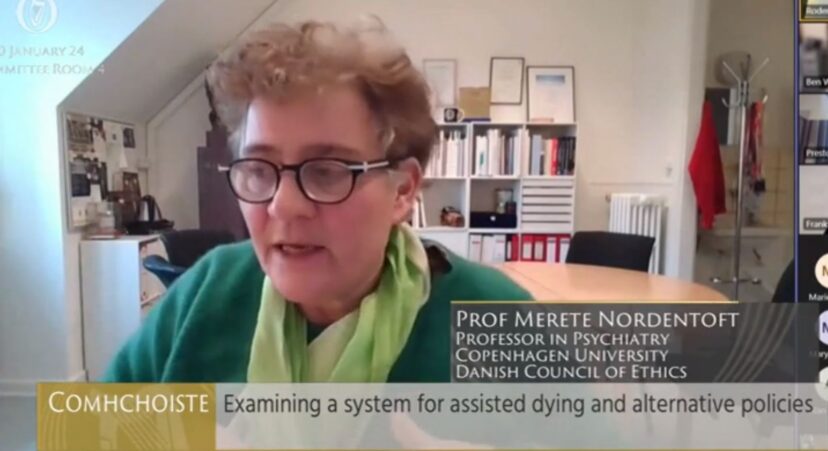

The Danish parliament has a Council of Ethics that sometimes reports to it on ethical issues. Recently it reported on euthanasia. Surprisingly perhaps – given Denmark’s reputation as a hyper-modern society – the Council recently voted overwhelmingly against recommending euthanasia or assisted suicide in any way, shape or form. Members of the Council of Ethics appeared before the Oireachtas Committee on Assisted Dying last week to explain their decision.

If euthanasia becomes an option, they said, “there is a great risk that it will become an expectation more than a right”.

The Committee was told: “The only thing that will be able to protect the lives and respect of those who are most vulnerable in society will be a ban without exceptions.”

Dr. Merete Nordentoft (pictured), professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen and a member of the Council, said: “There is a risk that it [euthanasia] will even be experienced as a duty”.

The potential societal impacts of legalising euthanasia were highlighted, including negative changes to perceptions of old age, disability, and quality of life.

“Assisted dying may cause unacceptable changes to basic norms for society and healthcare. The very existence of an offer of assisted dying will decisively change our ideas about old age, the coming of death, living with disability, quality of life and what it means to take others into account”, Prof. Nordentoft remarked.

In its written statement to the Oireachtas Committee, the Council of Ethics stated without ambiguity that only a total ban will protect the lives of the most vulnerable.

“We do not believe that legislation can be developed which will be able to function properly. We are concerned, particularly based on findings of developments in broad regimes of assisted dying, about the ability to adequately monitor and restrict the practice and possible expansions. The only thing that will be able to protect the lives and respect of those who are most vulnerable in society will be a ban without exceptions.”

As an expert in the field of suicide prevention, Prof. Nordentoft told the Committee about the often-changing nature of suicidal ideation and the importance of retaining the option to change one’s mind. Assisted suicide and euthanasia, instead, are irreversible and remove this possibility.

Also, it was noted that many patients undergoing palliative care may reassess their perception of a worthy life, suggesting that their desire for euthanasia may also evolve and reverse over time.

When asked about the apparent support for euthanasia among the Danish population, Prof. Nordentoft replied that this is often based on lack of proper knowledge of the current legal and medical situation. Many people believe that they will be forced to suffer against their will but, in Denmark as in Ireland, doctors are not obliged to provide life-prolonging treatment against a patient’s will, except in cases of psychosis and severe anorexia nervosa. Moreover, the use of medication to alleviate suffering, is allowed in palliative care, even when it may unintentionally shorten life.

The thoughtful recommendations provided by the Danish Council of Ethics should serve as a crucial consideration for legislators, urging them to reflect deeply on the outcomes and pitfalls observed in the Netherlands.

Indeed, the Netherlands is about to make euthanasia available to those between the ages of one and 12. For the time being, it will be only available to children in this age group with a terminal illness. Small babies can already be euthanised and so can anyone over 12. The change means that all age groups can now be killed via euthanasia. The logic of euthanasia is inexorable. Eventually, it covers everyone.