Today is the deadline for submissions to the Oireachtas Justice Committee concerning Gino Kenny’s ‘Dying with Dignity Bill’. What is happening in other countries that have gone this path becomes more relevant than ever. Euthanasia and assisted suicide were legalised in Canada in 2016 and, since then, the number of patients killed in hospitals and hospices has constantly increased. Like the examples of Belgium and Netherlands, it serves as a warning to us.

There have been more than 21,000 cases of assisted suicide and euthanasia in Canada since 2016 with constant, year-on-year increases to date.

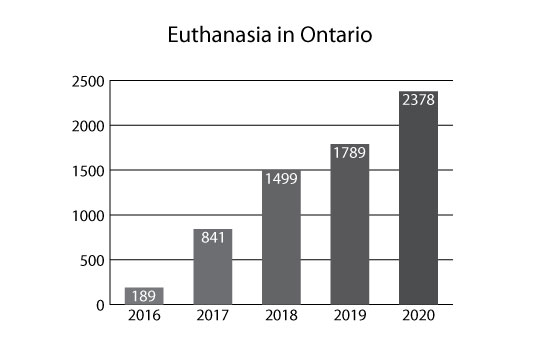

Here are the figures from Ontario, which represents 39pc of the Canada population: 189 (2016); 841 (2017); 1,499 (2018); 1,789 (2019); 2,378 (2020). Last year alone represents 33pc increase compared to 2019. It keeps growing and what is initially an exception becomes a social norm.

Canadian pro-life activists such as Alex Schadenberg of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition have said: “The numbers keep going up, and they will continue going up unless more people speak out about this and demand our politicians step back and reconsider what we are doing as a country”.

After only four years from its introduction, the law is already becoming more permissive and many safeguards are going to be removed soon. In December, the House of Commons in Canada passed a new Bill that will extend euthanasia to non-terminally ill patients. It will also permit a doctor or a nurse to inject patients incapable of consenting, if they were previously approved for euthanasia. It will remove the 10-day period, when death is deemed to be reasonably foreseeable. The Bill will be debated in the Canadian Senate in February and is likely to pass.

The Canadian case confirms that after euthanasia laws are introduced, safeguards are relaxed with time and criteria for eligibility become elastic.

The Gino Kenny Bill is aimed at those ‘likely to die’ from a terminal illness, but we see how quickly this can change once doctors are permitted to kill patients. The logic of ‘choice’ and avoiding ‘unbearable pain and suffering’ becomes inescapable.

The logic progresses not simply through changes in the law, like in Canada at the moment, but also with more permissive interpretation of the law by courts, review committees and professional bodies.

The consequences of introducing assisted suicide inevitably go beyond initial predictions.

For instance, the new law instituted in 2019 in the state of Victoria, in Australia, was presented as ‘moderate’ in comparison with similar legislations in the world. Yet, in the first year there were ten times the number of deaths expected. The initial estimate of 12 people became in reality 124 cases in one year and another 107 more death permits were issued. No one will be surprised if the numbers for 2020 show a further increase.

Victoria was the first Australian state to introduce euthanasia but, sadly, not the only one. The state of Western Australia followed, with a new law that will be in effect this year, and now the state of Tasmania is considering voluntary assisted dying while the Queensland government has announced a similar law to be introduced in May 2021. In New South Wales, an independent Bill is expected to be tabled in Parliament by mid-2021.

The Victoria euthanasia law seems to be having a domino effect on the rest of Australia. Neighbouring that New Zealand is following suit after a referendum last year.

If Ireland goes down this road, we will still be one of the first in Europe to do so.

The Gino Kenny Bill is presented as ‘moderate’. It’s not, because assisted suicide is an extreme act by definition that preys on the most vulnerable, which is why almost all palliative care doctors are against it.

But the Kenny Bill will only be the start. The grounds for assisted suicide, and its victims, will only widen from there.