New research just published in an academic journal suggests marriage may protect against the development of heart disease and stroke as well as influencing who is more likely to die of these diseases.

Researchers at Keele University in the UK drew on 34 previously published studies involving more than 2 million people aged 42-77 from all across the globe. Analysis of the data revealed that, compared with people who were married, those who were never married, divorced or widowed had a 42 per cent higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease and a 16 per cent higher risk of coronary artery disease. Not being married was also associated with a heightened risk of dying from both coronary heart disease (42 per cent) and stroke (55 per cent).

Further analysis shows divorce is associated with a 35 per cent higher risk of developing heart disease for both men and women, while widowers of both sexes were 16 per cent more likely to have a stroke. While there was no difference in the risk of death following a stroke between the married and the unmarried, this is not the case after a heart attack; the risk of which is significantly higher (42 per cent) among those who had never married.

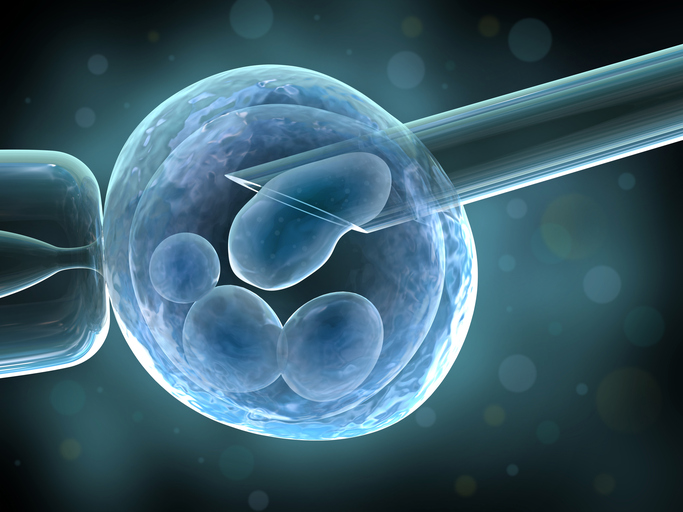

RTE’s Drivetime has asked if the use of donor eggs and sperm from anonymous sources raises ethical concerns given that those children will never know who their genetic parents are. The discussion took place against a background of controversy concerning falsification of adoption certificates by adoption societies in the past.

Mary Wilson interviewed a woman who used “double donor IVF” at age 46 to become pregnant with an embryo created from anonymous egg and sperm. She obtained the embryo in a private clinic in Prague in the Czech Republic where gamete donation must be anonymous by law. She said at the time she and her husband did not talk in detail about the consequences down the road for their child of his anonymous parentage: “it wasn’t something that caused us any consternation”. She did admit though that it does cause her “a small measure of concern”.

Dr Cathy Allen, a consultant obstetrician at Holles Street, said that people often go to the Czech Republic because “access is quite easy” and then they return to Holles Street for ante-natal care. Regarding anonymous donation, she said that doctors do not want to cause any harm, “but you likewise are not there to play God or be in judgement over people and what they decide is right for them and their families.”

She advised that legislation in this area should not be too-restrictive a she felt there is currently not good data on the subsequent welfare of the child, adding that people who say they are damaged may come from donor-conceived support groups and may well be biased. Dr Allen is herself a consultant with the private Merrion Fertility Clinic.

The Central Statistics Office (CSO) is assessing whether to recognise and record citizens who identify as neither male nor female in the next national census, with the traditional ‘binary choice’ likely to be widened by new definitions of gender.

The CSO has received a number of submissions from groups such as Transgender Equality Network Ireland and the organisation for young gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people named BeLonG To and have decided to assess the need for change in a series of smaller household surveys. They will be carried out in thousands of homes in the first three months of next year will include specific questions on gender.

A CSO statement to the Sunday Independent said: “CSO currently asks respondents to specify their sex, male or female. CSO has engaged with stakeholder groups to explore the development of statistics on gender identity. As part of this, CSO is planning an assessment of the inclusion of specific questions on gender identity in its household surveys.” These questions will be asked in a household survey on equality and discrimination.

The size of Ireland’s transsexual and inter-sex population is not known. The HSE defines transsexual as someone whose gender identity is ‘opposite’ to the sex ‘assigned’ to them at birth. Inter-sex is defined by the HSE as “individuals who cannot be classified using the medical norms of so-called male and female bodies”. The health authorities state that ‘gender fluid’ people experience different gender identities at different times. The HSE website states “A gender fluid person’s gender identity can be multiple genders at once, then switch to none, or move between single gender identities.”

The Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that law societies may deny accreditation to a Christian law school because of its Christian-based, campus code of ethics. Trinity Western University’s law school asks students and faculty to follow its “Community Covenant” based on biblical views of appropriate sexual behaviour on campus. This covenant was deemed discriminatory by some law societies, leading to a denial of accreditation.

While six Canadian provinces agreed to recognise the school’s graduates, Ontario denied recognition and Trinity Western appealed. In British Columbia, the local law society appealed. The British Columbia Court of Appeal ruled in favour of Trinity Western and stated that this case demonstrated how “a well-intentioned majority acting in the name of tolerance and liberalism, can, if unchecked, impose its views on the minority in a manner that is in itself intolerant and illiberal.” After the law society appealed, the Supreme Court heard both appeals together in December 2017. Last Friday they ruled in favour of the denial of accreditation. Two justices, Russell Brown and Suzanne Côté, dissented, expressing the view that “legislatively accommodated and Charter-protected religious practices, once exercised, cannot be cited by a state-actor as a reason justifying the exclusion of a religious community from public recognition.”

In an off-the-cuff talk on Saturday, Pope Francis compared the practice of aborting the disabled to Nazi ideology and reaffirmed that only the family founded on one man and one woman is the true image of God. Speaking to an Italian family association, the Pope said: “I’ve heard that it’s fashionable, or at least usual, that when in the first few months of pregnancy they do studies to see if the child is healthy or has something, the first proposal in such a case is, ‘Do we get rid of it?’”

This, he said, is “the murder of children…to get a peaceful life an innocent [person] is discarded”

Francis recalled that as a child he was horrified to hear stories from his teacher about children “thrown from the mountain” if they were born with malformations. “Today we do the same thing,” he said. “Last century, the whole world was scandalised by what the Nazis did to purify the race. Today, we do the same thing but with white gloves,” Francis said.

On the family, he noted that in modern society “one speaks of different types of family,” defining the term in different ways.

“Yes, it’s true that family is an analogous word, yes one can also say ‘the family of stars,’ ‘the family of trees,’ ‘the family of animals,’” he said, but stressed that “the family in the image of God is only one, that of man and woman…marriage is a wonderful sacrament.”

The Sinn Féin ardfheis has rejected a motion to allow its members a conscience vote on abortion, thereby imperiling the political futures of two of the bright stars of the pro-life movement.

Offaly TD, Carol Nolan, was the only TD in the Dáil to lose the party whip when she voted against holding the referendum to repeal the 8th Amendment. Peadar Tóibín, who was absent with permission from that vote, campaigned tirelessly to save the Eighth Amendment though he had to state the party’s official position in favour of repeal in every media appearance he made. He had previously lost the party whip in 2013 when he voted against the Fine Gael/Labour Abortion Act of that year. Both have indicated that they will also oppose the Government’s proposed legislation to make abortion available ‘on request’ up to 12 weeks, and on vague health grounds up to 24 weeks. The motion requesting that all “Sinn Féin members be allowed to articulate and vote on the issue of abortion in accordance with their conscience” was rejected by a majority of those present at the meeting which, unlike Fine Gael or Fianna Fáil, decides policy for the party.

A lawsuit involving a surrogate mother, a couple, a reality TV show and a little girl has shone a revealing light on some of the most objectionable aspects of the fertility industry. The US Bravo network host a reality TV series called ‘Flipping out’ which features a real estate agent and his partner. The gay couple recently decided to have a child and duly contracted the fertility industry to make their wish a reality. They bought an egg from a woman out of a catalogue, inseminated it with their own sperm, and had the resulting embryo gestated in the womb of another woman. They then filmed the birth, without the birth-mother’s permission. She is now suing them for gross invasion of privacy. Meanwhile, the little baby girl continues to feature on episodes of the TV show.

In a comment in the US Journal First Things, Brandon McGinley, said that whatever happens with the lawsuit, the little girl will always have been born on television, her childhood will always have been a marketable commodity and she “will always be the product of the will and the checkbook of two men who wanted a bespoke parenting experience.”

He continued: “Her name is Monroe Christine. She is a little girl who was paid for by two men. Her mother was picked out of a catalogue; the woman who gave birth to her was a contractually obligated guest star on a television show.”

Laws requiring Catholic priests to break the seal of confession passed the Canberra Territory’s legislature in Australia on June 7. The purpose of the Bill was to expand mandatory reporting of allegations of child abuse and misconduct to include religious organizations. The Archdiocese of Canberra and Goulburn has nine months to negotiate with the government on how it will work before the start of reportable conduct requirements.

Writing in The Canberra Times, Archbishop Christopher Prowse of Canberra and Goulburn said he supported the revised scheme, but would not support a requirement to break the Seal of Confession. He said such a requirement would neither help prevent abuse nor efforts to improve the safety of children in Catholic organisations.

In April, New South Wales Premier Gladys Berejiklian called for the Seal of Confession to be addressed by the Council of Australian Governments rather than state governments in isolation. “Our response to that recommendation (of the Royal Commission) is to take it through the COAG process. We believe that is the best way to deal with it,” she told the Australian Broadcasting Corp. “They’re complex issues that need to be balanced with what people believe to be religious freedoms,” the premier said.

Sex education should begin at three years old, according to an academic speaking before an Oireachtas committee on Tuesday. The Oireachtas education committee is reviewing how relationships and sexuality education (RSE) is taught in schools and will publish a report recommending how the curriculum can be changed. The wishes of parents have been given little attention in the hearings so far.

Dr Aoife Neary, of the University of Limerick, told the committee that sex education should begin at three when language around consent such as “I don’t like that” should be introduced. At this age, children should be told about family diversity and introduced to the concept of same-sex parents, she said. Dr Neary said that sex education should not be delayed because of concerns about “age appropriateness”.

Sarah Haslam, of the national youth development organisation Foróige, said sex education would not take away a child’s innocence. She said it had a sex education programme that could be adapted by schools while an RSE curriculum was being created.

Niall Behan, head of the Irish Family Planning Association (IFPA), said the current RSE curriculum exposed women to the risk of sexually transmitted infections and unplanned pregnancies, while Ms Neary said the curriculum was silent on gay and transsexual health and this needed to be addressed.

Jane Donnelly of Atheist Ireland told the committee the abortion referendum “changes everything” as it shows politicians “can no longer assume” that the majority of Catholic parents “want Catholic sex education for their children.”

Research in the US has shown that 63 percent of fathers who lived at home with a child ages 0 to 18 reported eating dinner with their child every day; an additional 27 percent reported doing the same at least several times a week. Only 8 percent of these fathers reported sharing dinner about once a week, less than once a week, or never. By contrast, for non-resident fathers a mere 4% ate dinner with their child every day; 29% did so several times a week; and 17% did so once a week, whereas 49% did so less than once a week or never.

The researchers with the think-tank Child Trends said that positive involvement from fathers is linked to many benefits for children, including better self-esteem, lower levels of depression, and greater academic success. “This involvement can include a range of behaviors. Eating meals together (most often dinner) provides a time and place for fathers (and indeed, all parents) to practice these positive parenting behaviors—and eating together is itself linked to a range of benefits for children”, said the authors of the research.